On April 4th, 2024, the Indiana Court of Appeals unanimously ruled that there is a religious liberty right to receive an abortion. Their opinion held that the state’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA)—a 2015 statute that exempts people of faith from Indiana laws that burden their religious practices—created a “right to exercise [one’s] sincere religious beliefs by obtaining an abortion when directed by their religion.” As the court explained, Indiana’s near-total abortion ban should not be enforced to prevent religiously motivated abortions. This case represents a rare victory for progressive or feminist religious liberty cases.

The opinion was a watershed moment—one of only a small handful of cases in U.S. legal history to recognize that faith can motivate patients to seek, rather than oppose, abortion. In other ways, however, the ruling was unremarkable.

The Christian Right has spent decades radically expanding the right to violate laws that conflict with one’s religious beliefs. The courts, however, have traditionally been more open to anti-abortion than abortion-affirming cases.

Religious Liberty for Progressives?

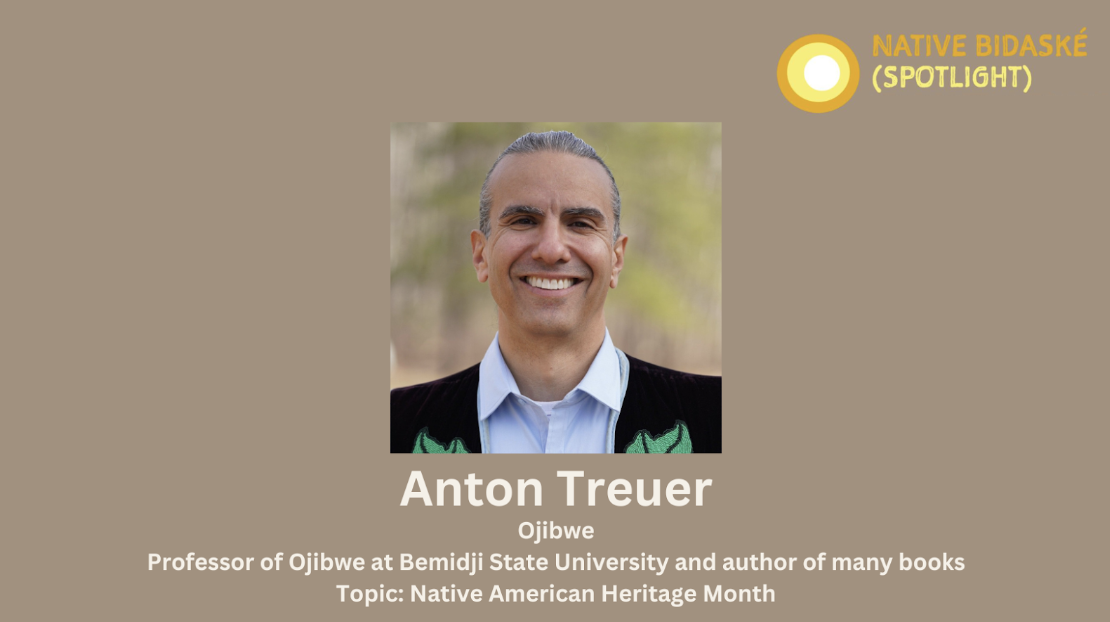

Religious people and communities have brought litigation to protect what we might call “progressive” faith practices for decades (though not all claimants involved have identified as progressive). Notable examples have included arguments by anti-Vietnam War activists that they were religiously motivated to destroy draft records; faith leaders who sought a religious right to perform weddings for same-sex couples when this was illegal; Native American tribes that have fought to protect their sacred sites from environmental damage; Muslims who challenged surveillance of their communities on religious liberty grounds; and a Seventh-day Adventist man who argued that his deportation would violate his family’s religious belief in family unity. In April of 2024, a group of faith leaders arrested while protesting a company that produces weapons used by the Israeli Defense Forces defended their actions as a form of religious exercise. Many cases have been brought, both before and after Roe v. Wade, demanding a religious liberty right to perform, access, or help facilitate abortion care.

Beyond the obvious theological distinctions, these cases, as I have written elsewhere, have significant differences with recent cases brought by conservative Christians. Most “progressive” religious liberty suits have been litigated by attorneys without dedicated experience or expertise in religion law, such as criminal defense lawyers, large corporate firms, or persons with experience in particular related issues such as tribal law or immigration. Further, they have typically been brought on a case-by-case basis—sometimes in response to the claimants’ arrest—rather than as part of a broader, organized litigation strategy.

Religious Liberty and the Christian Right

In contrast, the Christian Right has been engaged in a strategic, decades-long campaign to dramatically expand the right to religious exemptions. The Christian Right’s “religious liberty” strategy can be traced back at least to the Supreme Court’s 1990 decision Employment Division v. Smith. In this case, the Court held that the religious liberty of two members of the Native American Church was not violated when they were denied state unemployment benefits after having been fired for smoking peyote as part of a religious ritual. In so holding, the Court narrowed its interpretation of the Free Exercise Clause, which had been slowly expanding over the prior two decades. The Court explained that given religious diversity in the U.S., a broad right to religious exemptions would mean “courting anarchy.”

The Smith decision garnered significant backlash across the political spectrum. In 1993, a diverse coalition—spanning from the American Civil Liberties Union to the Traditional Values Coalition—banded together and attempted to reverse the impact of the holding by passing the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. This law, on which the Indiana RFRA was based, provides a broad legal right to religious exemptions from federal laws and policies.

The year after RFRA was passed, two conservative nonprofit law firms were founded explicitly to litigate religious liberty cases: Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF) and Becket. Today, the two firms have a combined annual income of over $125 million and employ nearly 100 attorneys. ADF also boasts over 4,500 allied “network attorneys,” training programs for lawyers and journalists, alliance networks to partner with and offer legal resources to churches, ministries, and businesses, and an international organization with additional funding and staff. Becket has partnered to provide clinical education to law students at prominent secular schools including Stanford and Harvard.

ADF and Becket both have established track records of fighting for exemptions from policies that protect reproductive rights and prohibit anti-LGBTQ and other forms of discrimination.

The firms have litigated numerous successful Supreme Court cases that effectively rolled back reproductive rights, including Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, National Institute for Family Life v. Becerra, and Burwell v. Hobby Lobby. They spearheaded cases that undermined LGBTQ and other civil rights, such as 303 Creative v. Elenis, Fulton v. Philadelphia, Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, and Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. EEOC. They have also fought to limit the reach of the Establishment Clause in cases such as Trinity Lutheran Church v. Comer and Town of Greece v. Galloway.

Further, they are only two of many conservative organizations dedicated to shaping the law, policy, and discourse of “religious liberty”; others include Liberty Counsel, First Liberty Institute, the Thomas More Society, and Christian Legal Society. The Right has made a substantial investment in litigating free exercise cases and, in doing so, developed a legal tool that has eroded access to health care and undermined our commitment to civil rights.

Religious Liberty in a Pluralistic Democracy

There has been no similar investment in religious liberty law by progressives or other groups outside the Christian Right since the passage of RFRA. If anything, there seems to be less progressive involvement in religious freedom law and policy than there was in the 1990s. This, in part, explains why progressive suits have been far more sporadic than conservative claims. Progressive religious liberty cases have also received far less public attention than suits brought by large, conservative firms with sizable communication teams. Even when progressive religious liberty claims have won, such as a series of cases finding that religious liberty rights protected the activities of people of faith who worked with migrants, they have failed to garner sustained recognition as part of a larger pattern.

While their cases may be fewer in number and too often ignored, progressive people of faith have long demanded legal protection for their own faith practices—from sheltering migrants to protesting war to helping people end unwanted pregnancies.

Such cases face challenges; however, in recent years especially, at least some courts have proved responsive to religious liberty claims brought by those outside the Christian Right. As the Indiana Court of Appeals explained, referencing the Supreme Court’s opinion in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby: “If a corporation can engage in a religious exercise by refusing to provide abortifacients…it stands to reason that a pregnant person can engage in a religious exercise by pursuing an abortion.”

The tide appears to be turning when it comes to religious right to abortion suits. In part, because the Christian Right has been so successful at conflating religiosity with opposition to abortion, these suits have garnered an enormous amount of interest—including, notably, from conservative religious liberty groups. Some conservative opponents of these suits have argued that if they win, policymakers will be more hesitant to adopt expansive religious exemption rights in the future. My response would be that if courts are unwilling to protect religious activities neutrally, then broad religious liberty laws must be reconsidered. To protect only the religious rights of conservatives would violate the commitment to religious neutrality enshrined in the Establishment Clause.

For far too long, well-funded law firms representing a select group of religious believers have overwhelmed the law, policy, and public discourse around “religious liberty.” As progressive faith communities garner more public attention—and legal wins—my hope is that they lead us on a path toward a more pluralistic and balanced approach to religious liberty.