By Jessica Wu

The development of qualified immunity reveals the doctrine’s incompatibility with civil rights. The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 first established the right to sue government officials for civil rights violations and Section 1983 claims. In 1967, at the end of the Civil Rights Movement, the Supreme Court introduced qualified immunity, limiting the right to sue police officers. In 1982, the Court expanded qualified immunity to eliminate the good faith requirement and raise the standard of liability so that conduct must violate “clearly established law.” Such a high legal standard effectively robs victims of civil rights violations from having their day in court, undermining the legal safeguard of civil rights.

Proponents of qualified immunity argue that it is essential to effective policing because it allows police officers to make split-second decisions without fear of lawsuits and that it does not prevent individuals from recovering damages. However, qualified immunity often plays out as an absolute shield against civil liability. Justice Sotomayor’s dissent in Mullenix v. Luna, 577 U.S. 7 (2015) describes the Court’s acceptance of qualified immunity as sanctioning a “shoot first, think later” approach to policing that renders the protection of the Fourth Amendment “hollow.”

The murder of George Floyd spurred protests against police violence and calls for reform, including the elimination of qualified immunity. In 2020, Colorado passed Senate Bill 20-217, the Enhance Law Enforcement Integrity Act (ELEIA), abolishing qualified immunity as a defense for police officers in state courts, the first state to do so. From 2021 to 2023, litigants took advantage of state courts to file claims of constitutional rights violations, filing a total of 82 suits. However, Section 1983 federal court filings against Colorado officers did not decrease from 2018 to 2023. There are many reasons for that, including the likelihood of a delayed impact and the fact that ELEIA does not retroactively apply to conduct. Nevertheless, given qualified immunity’s history as an absolute shield, the Colorado legislation successfully provided opportunities for 82 claims to be heard in state courts that otherwise might not have been available under Section 1983.

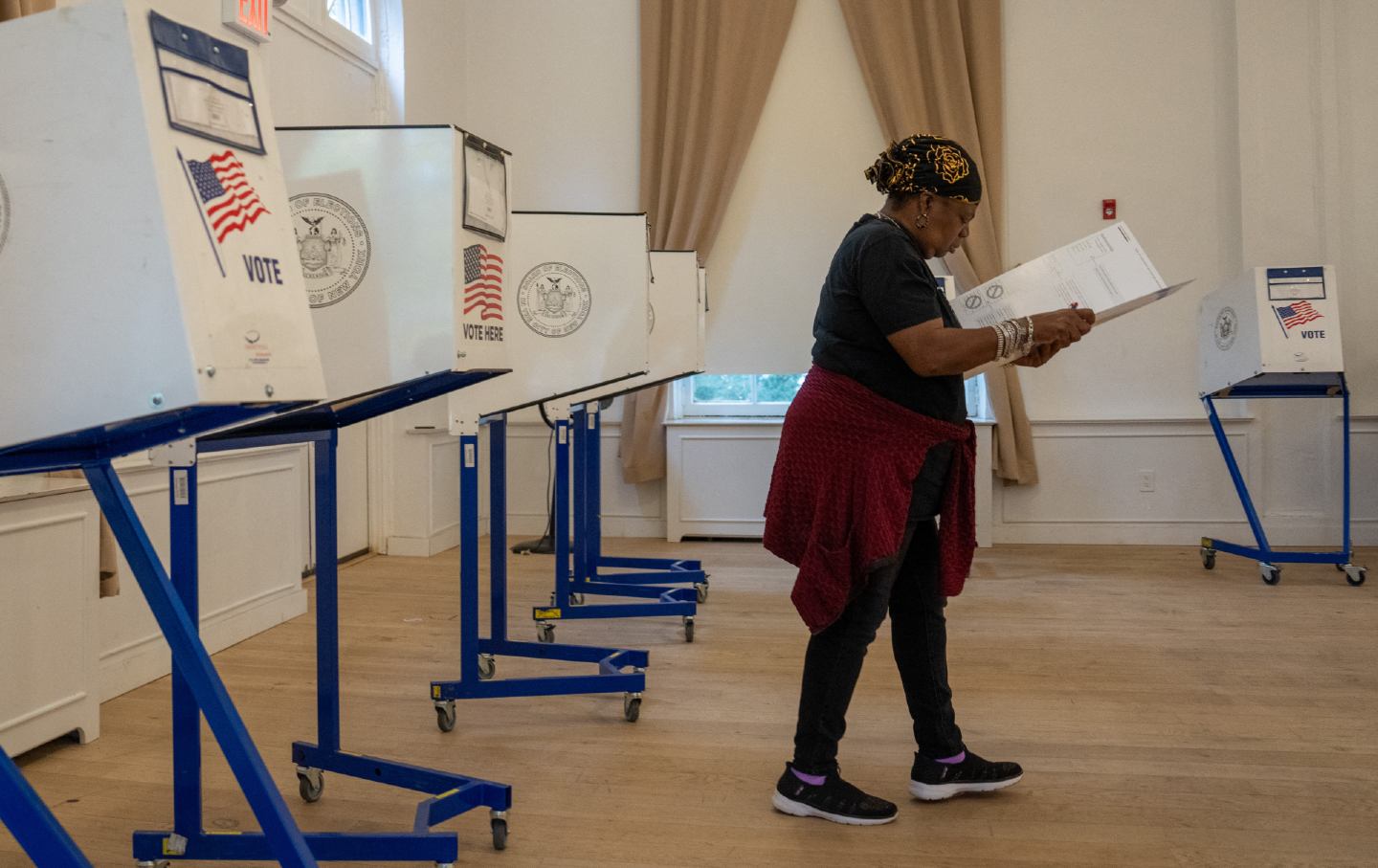

Photo: Matt Popovich via Unsplash

Moreover, SB 20-217 has had effects aside from the caseload of constitutional right violation suits. The legislation created the crime of failing to intervene in another officer’s excessive use of force, under which two police officers have been convicted. Additionally, the Colorado Peace Officer Standards and Training Board created a database of officers who have been untruthful, criminally investigated, terminated for cause, or revoked of their certification. Furthermore, all Colorado agencies were trained on stricter use-of force laws, aligning with the widespread trend towards stricter use of force laws.

Since 2020, six states limited or banned immunity for police officers in civil rights lawsuits. While the full impacts of limiting qualified immunity are yet to be determined, it is certainly a step on the right track towards accountability, which is a necessary component for ensuring civil rights.

All blog posts are opinion pieces produced by Associate Editors, and any and all beliefs expressed solely reflect the view(s) of the individual author. These publications do not reflect the official view(s) of the Law Journal for Social Justice, or any other organization, institution, or individual.